Between 1770 and 1773, the Danish government abolished state censorship, enacting freedom of the press throughout the country. This brought about thousands of short booklets - called pamphlets - touching upon the everyday life of citizens. These documents have been digitized and made available in 2020 for the 250th anniversary of abolishing censorship, supported by the Carlsberg Foundation.

As a university project, together with two other students, we had to design a search user interface for exploring the documents. The goal was to create a digital archive of the pamphlets for both an academic audience (researchers and history students) and non-professionals interested in the collection.

Pamphlets are non-professional publications that cover many unrelated topics at once, which makes them difficult to comprehend. Though the content of these documents provide valuable information for historians, the collection was too vast to conduct historical research manually across the writings.

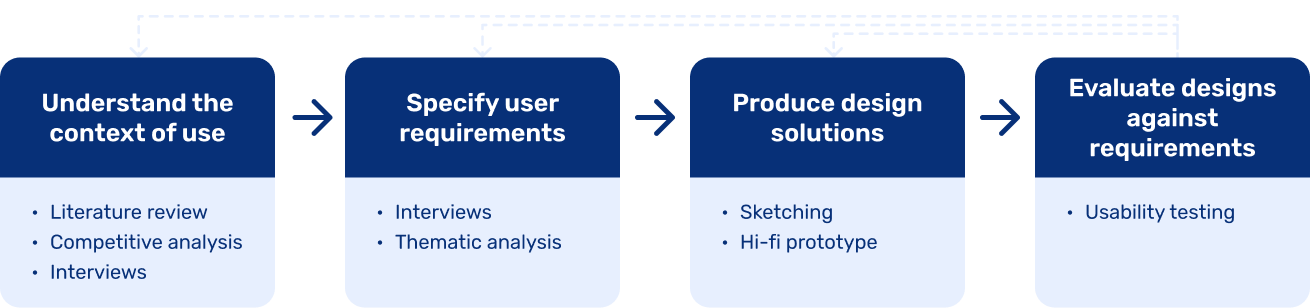

As none in the team had experience with designing search user interfaces used for academic purposes, we needed a framework to structure our research and design activities around. Based on contemporary literature, human-centered design was the most recommended process to follow, so I outlined a project plan according to it.

To get a grasp of the domain area, I read dozens of research publications to understand what makes a good digital archive. A recurring topic across the literature was that the system must allow serendipitous exploration: besides only targeted lookups (i.e. trying to find a specific document), users can browse the archive nonlinearly and without a clear item in mind that they want to find.

Another important aspect was utilizing the digital format and allowing quantitative analysis of the documents to augment historical research.

To get an overview of best practices and gather inspiration, I reviewed 31 digital archives and noted the various search functionalities they provide.

The analysis helped us create an inventory of must-have features (i.e., if they were present in more than ~50% of the digital archives) and gather ideas for advanced search functionalities (present in less then ~25% of archives). Interestingly, only 63% of digital archives provided some kind of advanced search feature — an opportunity for us to provide a richer search experience than what scholars are used to.

To tailor the system to the needs of our target audience, we conducted interviews and contextual inquiries with 2 history professors who specialized in researching pamphlets. We also interviewed a student enrolled to a BA course in history, to cover a wider range of user needs.

We interviewed two historians to learn about the historical background of the document collection, then provided them stimulus material (printed copies of two pamphlets and someoffice supplies like markers and highlighters) and asked them to demonstrate how they practice historical research.

We asked the history BA student about how they learn about a new field of history and how they use digital archives or libraries when preparing school assignments.

We transcribed the interviews and conducted a thematic analysis to discover relevant patterns within the data. We collected user quotes that denoted user needs or problems, codified them with keywords or short sentences, and grouped them into themes. This gave us an overview of the domain-specific user needs and difficulties users face during historical research.

We gathered all requirements we identified during the competitive analysis and the user research, then each of us set out to create sketches to ideate about design solutions. But first, to set a baseline of the ideation scope, we agreed on the overall information architecture of the digital archive.

To ensure an experience that users are familiar with, we first decided on a page architecture that matches the majority of digital archives we reviewed previously. This included a landing page, search user interface, document details view, and a separate collection of views for data visualizations to facilitate exploratory searching.

After agreeing on the overarching page structure, each team member ideated separately on functionalities that cater to the uncovered user needs.

After deciding on what functionalities to include and where, I set out to create sketches of how the UI could look like.

We compared our sketches and evaluated the ideas against each other, based on their potential to cater for the user needs we identified earlier. After evaluating the ideas, I created a mid-fidelity prototype encompassing the best solutions we agreed on.

We reached out to one of the history professors we interviewed earlier to test our prototype and get their feedback about whether and how the solution might fit into his workflow when conducting historical research. We asked them to start with a simple query search, then try to visualize the result set, and finally to make a comparison to a separate query.

Some of the most important learnings were:

Showing the document transcript next to the scanned image is great, and helps with reading. Crowdsourced annotations are also a great idea, especially if other historians could reference them.

Visualizations could be really useful, especially for students who are learning about the historical period, because these visual summaries can help them get an overview.

Annotating each document with topical tags would not make sense because the number of topics a pamphlet may cover can be excessively long.

After usability testing the prototype further with at least 4 more historians or other field experts, the next phase would include gauging the user needs of potential non-expert users, e.g. students or history hobbyists - through another round of generative research.

During implementation, special attention would be paid to content localization, as most users are expected to be Danish - and most user content would also likely be created in Danish. Crowdsourcing annotations also requires a selective account creation process, so that only qualified experts can contribute.

The Human-Centered Design framework proved to be a great guidance into establishing and structuring our research and design activities. Due to the timeframe and the scope (and the project being a school assignment), we could not commit to iterations. Injecting a low-fidelity prototyping-and-testing phase would have helped us to better refine the final solution, and involving more users in the generative interviews and observations would have given us richer user insights.